Let's be charitable, though: is there any way to defend what these seemingly inconsistent people said?

Friday, February 27, 2009

Consistent as a Contradiction

Let's be charitable, though: is there any way to defend what these seemingly inconsistent people said?

Thursday, February 26, 2009

An Expert for Every Cause

Next, here's an interesting article on a great question: How are non-specialists supposed to figure out the truth about stuff that requires expertise?

Not all alleged experts are actual experts. Here's a method to tell which experts are phonies.

Here's a Saturday Night Live sketch in which Christopher Walken completely flunks the competence test.

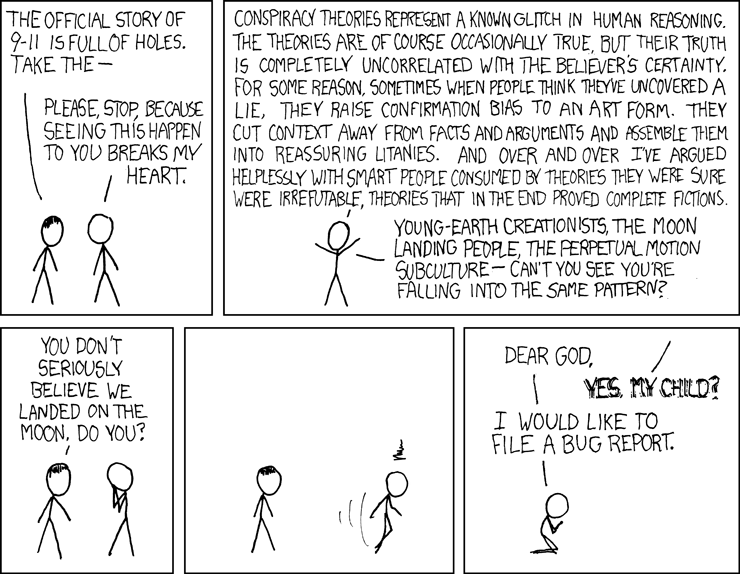

Finally, here's that article on the 9/11 conspiracy physicist that we talked about in class. I've quoted an excerpt of the relevant section on the lone-wolf semi-expert (physicist) versus the overwhelming consensus of more relevant experts (structural engineers):

While there are a handful of Web sites that seek to debunk the claims of Mr. Jones and others in the movement, most mainstream scientists, in fact, have not seen fit to engage them.And one more excerpt on reasons to be skeptical of conspiracy theories in general:

"There's nothing to debunk," says Zdenek P. Bazant, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Northwestern University and the author of the first peer-reviewed paper on the World Trade Center collapses.

"It's a non-issue," says Sivaraj Shyam-Sunder, a lead investigator for the National Institute of Standards and Technology's study of the collapses.

Ross B. Corotis, a professor of civil engineering at the University of Colorado at Boulder and a member of the editorial board at the journal Structural Safety, says that most engineers are pretty settled on what happened at the World Trade Center. "There's not really disagreement as to what happened for 99 percent of the details," he says.

One of the most common intuitive problems people have with conspiracy theories is that they require positing such complicated webs of secret actions. If the twin towers fell in a carefully orchestrated demolition shortly after being hit by planes, who set the charges? Who did the planning? And how could hundreds, if not thousands of people complicit in the murder of their own countrymen keep quiet? Usually, Occam's razor intervenes.

Another common problem with conspiracy theories is that they tend to impute cartoonish motives to "them" — the elites who operate in the shadows. The end result often feels like a heavily plotted movie whose characters do not ring true.

Then there are other cognitive Do Not Enter signs: When history ceases to resemble a train of conflicts and ambiguities and becomes instead a series of disinformation campaigns, you sense that a basic self-correcting mechanism of thought has been disabled. A bridge is out, and paranoia yawns below.

Wednesday, February 25, 2009

Maybe It'll Taste Good This Year...

Here's some random stuff related to inductive arguments. First, here's a video of Lewis Black describing his failure to reason inductively every year around Halloween:

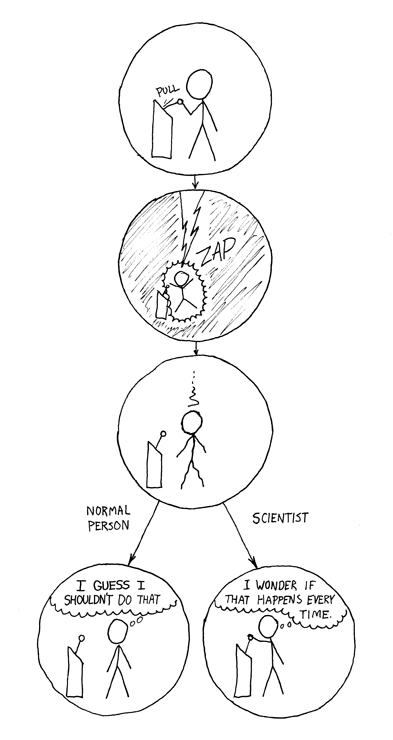

Also, here's a stick figure comic about scientists' impulse to get a big enough sample.

Thursday, February 19, 2009

Inductive & Abductive Args

Inductive Args

1) The three people I talked to at The Roots concert told me they hated the opening act Talib Kweli. Therefore, nobody at the concert liked the opening act.

This argument is overall bad because of the small sample size. We don't know exactly how many people went to the concert. Still, given what we know about concerts and the popularity of The Roots, we can probably safely conclude that the crowd was at least in the hundreds. A sample of 3 given this probable overall population is too small.2) Every time I’ve seen a rolling billiard ball hit a stationary billiard ball, the stationary ball starts moving. So the next time I roll one billiard ball into another, the stationary one will move when hit.

This argument is overall good. Again, we don't know the exact numbers on this. We don't even know who the person making the argument is. Still, if we start with the assumption that the person making this argument is typical, we can probably safely conclude that she or he has watched or played pool a decent amount. So our sample is probably hundreds or thousands of billiard ball collisions.3) Brandon Rush averaged around 13 points a game the past three years playing college basketball for Kansas. So I expect him to average 13 points a game when he plays in the NBA this year.

Also, each billiard ball collision is fairly representative of pool ball collisions in general. This seems to be a good example of the principle of "You've seen it once, you've seen them all."

This argument is overall bad. The sample is actually large enough: Rush played close to 40 games each season in college. However, the sample of college game performance is not representative of NBA performance. Since there are better players and tougher competition in the NBA than there are in college, most players do not perform as well statistically in the pros as they did in college.Abductive Args

1) In a recent study, 100% of those who took a new birth control pill didn’t get pregnant. Only males participated in the study. Thus, the birth control pill must be very effective.

This argument is overall bad. Concluding ing that this pill effectively prevents pregnancy is not the best explanation of the evidence we have. One big background assumption we have is that males do not get pregnant. Hypothesizing that the participants didn't get pregnant because they are male is a much better explanation of the evidence, since it matches our expectations more.(Scientists are actually developing a male birth control pill. But this, of course, prevents men from getting their female sexual partners pregnant. There isn't a need for something that prevents the men themselves from getting pregnant... or is there?)

Wednesday, February 18, 2009

Possible Paper Articles

Bad Stereotyping

race & gender = insufficient info

The Idle Life is Worth Living

in praise of laziness

In the Basement of the Ivory Tower

are some people just not meant for college?

The Financial Crisis Killed Libertarianism

if it wasn't dead to begin with

Consider the Lobster

David Foster Wallace ponders animal ethics

Who Would Make an Effective Teacher?

we're using the wrong predictors

Loyalty is Overrated

adaptability & autonomy matter more

FBI Profiling

it's a scam, like cold reading

Singer: How Much Should We Give?

just try to think up a more important topic

The Dark Art of Interrogation

Bowden says torture is necessary

Can Foreign Aid Work?

Kristof says it has problems, but we should use it

Against Free Speech

but it's free, so it must be good

You Don't Deserve Your Salary

no one does

What pro-lifers miss in the stem-cell debate

love embryos? then hate fertility clinics

Is Worrying About the Ethics of Your Diet Elitist?

since you asked, no

Is Selling Organs Repugnant?

freakonomicists for a free-market for organs

Should I Become a Professional Philosopher?

hell 2 da naw

Blackburn Defends Philosophy

it beats being employed

Tuesday, February 17, 2009

Paper Guidelines

Worth: 5% of final grade

Length/Format: Papers must be typed, and must be between 300-600 words long. Provide a word count on the first page of the paper. (Most programs like Microsoft Word & WordPerfect have automatic word counts.)

Assignment:

1) Pick an article from a newspaper, magazine, or journal in which an author presents an argument for a particular position. I will also provide some links to potential articles at the course website. You are also free to choose any article on any topic you want, but you must show Sean your article by Friday, March 6th, for approval. The main requirement is that the author of the article must be presenting an argument. One place to look for such articles is the Opinion page of a newspaper. Here’s a short list of some other good sources online:

- The New Yorker

- Slate

- New York Review of Books

- London Review of Books

- Times Literary Supplement

- Boston Review

- Atlantic Monthly

- The New Republic

- The Weekly Standard

- The Nation

- Reason

- Dissent

- First Things

- Mother Jones

- National Journal

- The New Criterion

2) In the essay, first briefly explain the article’s argument in your own words. What is the position that the author is arguing for? What are the reasons the author offers as evidence for her or his conclusion? What type of argument does the author provide? In other words, provide a brief summary of the argument.

NOTE: This part of your paper shouldn’t be very long. I recommend making this about one paragraph of your paper.

3) In the essay, then evaluate the article’s argument. Overall, is this a good or a bad argument? Why or why not? Check each premise: is each premise true? Or is it false? Questionable? (Do research if you have to in order to determine whether the author’s claims are true.) Then check the structure of the argument. Do the premises provide enough rational support for the conclusion? If you are criticizing the article’s argument, be sure to consider potential responses that the author might offer, and explain why these responses don’t work. If you are defending the article’s argument, be sure to consider and respond to objections.

NOTE: This should be the main part of your paper. Focus most of your paper on evaluating the argument.

4) Attach a copy of the article to your paper when you hand it in. (Save trees! Print it on few pages!)

TIP: It’s easier to write this paper on an article with a BAD argument. Try finding a poorly-reasoned article!

TIP: It’s easier to write this paper on an article with a BAD argument. Try finding a poorly-reasoned article!

Monday, February 16, 2009

Structure

An argument's structure is its underlying logic; the way the premises and conclusion logically relate to one another. The structure of an argument is entirely separate from the actual meaning of the premises. For instance, the following three arguments, even though they're talking about different things, have the exact same structure:

1) All tigers have stripes.

Tony is a tiger.

Tony has stripes.

2) All humans have wings.

Sean is a human.

Sean has wings.

3) All blurgles have glorps.

Xerxon is a blurgle.

Xerxon has glorps.

There are, of course, other, non-structural differences in these three arguments. For instance, the tiger argument is overall good, since it has a good structure AND true premises. The human/wings argument is overall bad, since it has a false premise. And the blurgles argument is just crazy, since it uses made up words. Still, all three arguments have the same underlying structure (a good structure):

All A's have B's.

x is an A.

x has B's.

Evaluating the structure of an argument is tricky. Here's the main idea regarding what counts as a good structure: the premises, if they were true, would provide good evidence for us to believe that the conclusion is true. So, if you believed the premises, they would convince you that the conclusion is worth believing, too.

Note I did NOT say that the premises are actually true in a good-structured argument. Structure is only about truth-preservation, not about whether the premises are actually true or false. What's "truth preservation" mean? Well, truth-preserving arguments are those whose structures guarantee that if you stick in true premises, you get a true conclusion.

The premises you've actually stuck into this particular structure could be good (true) or bad (false). That's what makes evaluating an arg's structure so weird. To check the structure, you have to ignore what you actually know about the premises being true or false.

Good Structured Deductive Args (Valid)

If we assume that all the premises are true, then the conclusion must also be true for an argument to have a good structure. Notice we are only assuming truth, not guaranteeing it. Again, this makes sense, because we’re truth-preservers: if the premises are true, the conclusion that follows must be true.

EXAMPLES:

1) All humans are mammals.

All mammals have hair.

All humans have hair.

2) If it snows, then it’s below 32 degrees.

It is snowing right now.

It’s below 32 degrees right now.

3) All humans are mammals.

All mammals have wings.

All humans have wings.

4) Either Yao is tall or Spud is tall.

Yao is not tall.

Therefore, Spud is tall.

Even though arguments 3 and 4 are ultimately bad, they still have good structure (their underlying form is good). The second premise of argument 3 is false—not all mammals have wings—but it has the same exact structure of argument 1—a good structure. Same with argument 4: the second premise is false (Yao Ming is about 7 feet tall), but the structure is good (it’s either this or that; it’s not this; therefore, it’s that).

To evaluate the structure, then, assume that all the premises are true. Imagine a world in which all the premises are true. In that world, MUST the conclusion also be true? Or can you imagine a scenario in that world in which the premises are true, but the conclusion is still false? If you can imagine this situation, then the argument's structure is bad. If you cannot, then the argument is truth-preserving (inputting truths guarantees a true output), and thus the structure is good.

Bad Structured Deductive Args (Invalid)

In an argument with a bad structure, you can’t draw the conclusion from the premises – they don’t naturally follow. Bad structured arguments do not preserve truth.

EXAMPLES:

1) All humans are mammals.

All whales are mammals.

All humans are whales.

2) If it snows, then it’s below 32 degrees.

It doesn’t snow.

It’s not below 32 degrees.

3) All humans are mammals.

All students in our class are mammals.

All students in our class are humans.

4) Either Yao is tall or Spud is short.

Yao is tall.

Spud is short.

Even though arguments 3 and 4 have all true premises and a true conclusion, they are still have a bad structure, because their form is bad. Argument 3 has the same exact structure as argument 1—a bad structure (it doesn’t preserve truth).

Even though in the real world the premises and conclusion of argument 3 are true, we can imagine a world in which all the premises of argument 3 are true, yet the conclusion is false. For instance, imagine that our school starts letting whales take classes. The second premise would still be true, but the conclusion would then be false.

The same goes for argument 4: even though Spud is short (Spud Webb is around 5 feet tall), this argument doesn’t guarantee this. The structure is bad (it’s either this or that; it’s this; therefore, it’s that, too.). We can imagine a world in which Yao is tall, the first premise is true, and yet Spud is tall, too.

Sunday, February 15, 2009

Understanding Args

1. (P1) Fairdale has the best team.

(C) Fairdale will win the championship

2. (P1) The housing market is depressed.

(P2) Interest rates are low.

(C) It's a good time to buy a home.

3. (P1) China is guilty of extreme human rights abuses.

(P2) China refuses to implement democratic reforms.

(C) The U.S. should refuse to deal with the present Chinese government.

4. (P1) The results of the Persian Gulf War were obviously successful for the U.S. military.

(C) The U. S. military is both capable and competent.

5. (P1) Scientific discoveries are continually debunking religious myths.

(P2) Science provides the only hope for solving the many problems faced by humankind.

(C) Science provides a more accurate view of human life than does religion.

6. (P1) Freedom of speech and expressions are essential to a democratic form of government.

(P2) As soon as we allow some censorship, it won't be long before censorship will be used to silence the opinions critical of the government.

(P3) Once we allow some censorship, we will have no more freedom than the Germans did under Hitler.

(C) We must resist all effort to allow the government to censor entertainment.

7. (P1) I'm very good at my job.

(C) I deserve a raise.

8. (P1) Jesse is one year old.

(P2) Most one-year-olds can walk.

(C) Jesse can walk.

9. (P1) The revocation of the 55 mph speed limit has resulted in an increased number of auto fatalities.

(C) we must alleviate this problem with stricter speed limit enforcement.

10. (P1) The last person we hired from Bayview Tech turned out to be a bad employee.

(C) I'm not willing to hire anybody else from that school again.

11. (P1) Maebe didn't show up for work today.

(P2) Maebe has never missed work unless she was sick.

(C) Maebe is probably sick today.

12. (P1) The United States, as the most powerful nation in the world, has a moral obligation to give assistance to people who are subjected to inhumane treatment.

(P2) The ethnic Albanians were being persecuted in Kosovo.

(C) It was proper for the U.S. to become involved in the air campaign against Kosovo.

----------------

Hat tip: I took some of the examples (with some revisions) from Beth Rosdatter's website , and some (with some revisions) from Jon Young's website .

Thursday, February 12, 2009

How Many Are Those Doggies In the Window?

Here's a map the top ten pet dog populations by country (although there's no source on this map's estimates, so caveat emptor):

Also, some dogs do not bark. That's why, in the inductive argument we discussed in class, I was careful to conclude only that "Most dogs bark," not "All dogs bark."

One more random fun fact: they used 217 dalmations to film the live-action remake of 101 Dalmations.

Hey, this is too much focus on dogs for my taste.

Tuesday, February 10, 2009

Monday, February 9, 2009

Quiz You Once, Shame on Me...

The quiz is on what we have discussed in class from Chapters 1 and 2 of the textbook. Specifically, here's what will be covered on the quiz:

- arguments in general

- deductive args (valid & sound)

- fancier deductive args

- statements: contradictions, tautologies, contingencies

- inductive args

- abductive args (inferences to the best explanation)

The quiz is worth 7.5% of your overall grade. Feel free to insult me in the comments for putting you through the terrible ordeal of taking a quiz.

Saturday, February 7, 2009

Join the Club!

We're having our first meeting at 7:00 p.m. on Wednesday, February 11th, at Coffee Works in Voorhees. Students from most of the schools I've taught at are planning to attend.

Check it out! If you're interested, feel free to join us.

Friday, February 6, 2009

Evaluating Deductive Args

1) All kangaroos are marsupials.

All marsupials are mammals.

All kangaroos are mammals.

P1- true2) (from Stephen Colbert)

P2- true

structure- valid

overall - sound

Bush was either a great prez or the greatest prez.

Bush wasn’t a great prez.

Bush was the greatest prez.

P1- questionable ("great" is subjective)3) Some people are funny.

P2- questionable ("great" is subjective)

structure- valid (it's either A or B; it's not A; so it's B)

overall- unsound (bad premises)

Sean is a person.

Sean is funny.

P1- true (we might disagree over who specifically is funny, but nearly all of us would agree that someone is funny)4) All email forwards are annoying.

P2- true

structure- invalid (the 1st premise only says some are funny; Sean could be one of the unfunny people)

overall- unsound (bad structure)

Some email forwards are false.

Some annoying things are false.

P1- questionable ("annoying" is subjective)5) All bats are mammals.

P2- true

structure- valid (the premises establish that some email forwards are both annoying and false; so some annoying things [those forwards] are false)

overall - unsound (bad first premise)

All bats have wings.

All mammals have wings.

P1- true6) Some dads have beards.

P2- true (if interpreted to mean "All bats are the sorts of creatures who have wings.") or false (if interpreted to mean "Each and every living bat has wings," since some bats are born without wings)

structure- invalid (we don't know anything about the relationship between mammals and winged creatures just from the fact that bats belong to each group)

overall- unsound (bad structure)

All bearded people are mean.

Some dads are mean.

P1- true7) This class is boring.

P2- questionable ("mean" is subjective)

structure- valid (if all the people with beards were mean, then the dads with beards would be mean, so some dads would be mean)

overall- unsound (bad 2nd premise)

All boring things are taught by Sean

This class is taught by Sean.

P1-questionable ("boring" is subjective)8) All students in here are mammals.

P2- false (nearly everyone would agree that there are some boring things not associated with Sean)

structure- valid

overall- unsound (bad premises)

All humans are mammals.

All students in here are humans.

P1- true

P2- true

structure- invalid (the premises only tell us that students and humans both belong to the mammals group; we don't know enough about the relationship between students and humans from this; for instance, what if a dog were a student in our class?)

overall- unsound (bad structure)

All wasps are insects.

All insects are scary.

All hornets are scary.

P1- true!10) All students in here are humans.

P2- true

P3- questionable ("scary" is subjective)

structure- valid

overall- unsound (bad 3rd premise)

All humans are shorter than 10 feet tall.

All students in here are shorter than 10 feet tall.

P1- true11) If Sean sings, then students cringe.

P2- true!

structure- valid (same structure as arg #1)

overall- sound

Sean is singing right now.

Students are cringing right now.

P1- questionable (since you haven't heard me sing, you don't know whether it's true or false)12) If Sean sings, then students cringe.

P2- false

structure- valid

overall- unsound (bad premises)

Sean isn't singing right now.

Students aren't cringing right now.

P1- questionable (again, you don't know)13) If Sean sings, then students cringe.

P2- true

structure- invalid (from premise 1, we only know what happens when Sean is singing, not when he isn't singing; students could cringe for a different reason)

overall- unsound (bad 1st premise and structure)

Students aren't cringing right now.

Sean isn't singing right now.

P1- questionable (again, you don't know)14) If Sean sings, then students cringe.

P2- true

structure- valid

overall- unsound (bad 1st premise)

Students are cringing right now.

Sean is singing right now.

P1- questionable (again, you don't know)

P2- false

structure- invalid (from premise 1, we only know that Sean singing is one way to guarantee that students cringe; just because they're cringing doesn't mean Sean's the one who caused it; again, students could cringe for a different reason)

overall- unsound (bad premises and structure)

(More on Sisyphus)

Tuesday, February 3, 2009

Homework #1

DIRECTIONS: Provide original examples of the following types of arguments (in premise/conclusion form), if possible. If it is not possible, explain why.

1. A valid deductive argument with one false premise.

2. An invalid deductive argument with all true premises.

3. An unsound deductive argument that is valid.

4. A sound deductive argument that is invalid.

MULTIPLE CHOICE: Circle the correct response. Only one answer choice is correct.

5. If a deductive argument is unsound, then:

a) its conclusion must be false.

b) its conclusion must be true.

c) its conclusion could be true or false.

6. If a deductive argument is unsound, then:

a) it must be valid.

b) it must be invalid.

c) it could be valid or invalid.

7. If a deductive argument is unsound, then:

a) at least one premise must be false.

b) all the premises must be false.

c) all the premises must be true.

d) not enough info to determine.

8. If a deductive argument’s conclusion is true:

a) then the argument must be valid.

b) then the argument must be invalid.

c) then the argument could be valid or invalid.

9. If a deductive argument is sound, then:

a) its conclusion must be true.

b) its conclusion must be false.

c) its conclusion could be true or false.

10. If a deductive argument is sound, then:

a) it must be valid.

b) it must be invalid.

c) it could be valid or invalid.

11. If a deductive argument is sound, then:

a) at least one premise must be false.

b) all the premises must be false.

c) all the premises must be true.

d) not enough info to determine.

12. If a deductive argument’s conclusion is false:

a) then the argument must be valid.

b) then the argument must be invalid.

c) then the argument could be valid or invalid.